Also Read

The Rape Of The Lock is a poem in which Alexander Pope shows himself empathetically as the spokesman of his age. This poem pictures, the artificial tone of the age and the frivolous aspect of femininity. We see in this poem the elegans and the emptiness, the meanness and the vanity, the jealousies, treacherous and intrigues of the social life of the aristocracy of the 18th century.

As a social satire at the very outset we become acquainted with the idleness late rising and fondness for domestic pets of the aristocratic ladies of that time. Belinda woke up at the hour of twelve and then falls asleep again. At the same time we also become acquainted about the superficiality of the ladies who loved gilded chariots loved the game of ombre and cards.

Aristocratic ladies treated there dressing table as their chief concern. The women of the time felt glad to receive love letters. Levity was the hallmark there manners being totally artificial and affected. On those days a frail China jar receiving crack is equated with a lady's losing her chastity. A lady's staining her honour is considered as serious as staining new necklace. And loosing a necklace, and the death of a lap dog or the barking of a rich vessel was as serious matter to the lady as the death of her husband. All those vanities is and trifles on the part of the contemporary 18th century aristocratic ladies have well been scratched in the poem represented by Belinda.

The aristocratic young man of the time were like the ladies, lacking in any serious purpose or morality. There was a keen competition among them to win feminine flavours. The life of the contemporary lords was as empty and shallow as the life of the ladies. The shallowness and superficiality of the time where also clear from the kind of gossip that went on at the court. Card parties where common, ombre was the favourite game among Lords and ladies, coffee drinking was another most important diversion of the time.

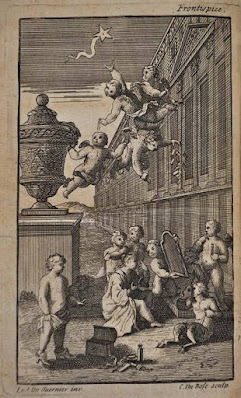

|

| The Rape Of The Lock |

As a social satire at the very outset we become acquainted with the idleness late rising and fondness for domestic pets of the aristocratic ladies of that time. Belinda woke up at the hour of twelve and then falls asleep again. At the same time we also become acquainted about the superficiality of the ladies who loved gilded chariots loved the game of ombre and cards.

Aristocratic ladies treated there dressing table as their chief concern. The women of the time felt glad to receive love letters. Levity was the hallmark there manners being totally artificial and affected. On those days a frail China jar receiving crack is equated with a lady's losing her chastity. A lady's staining her honour is considered as serious as staining new necklace. And loosing a necklace, and the death of a lap dog or the barking of a rich vessel was as serious matter to the lady as the death of her husband. All those vanities is and trifles on the part of the contemporary 18th century aristocratic ladies have well been scratched in the poem represented by Belinda.

The aristocratic young man of the time were like the ladies, lacking in any serious purpose or morality. There was a keen competition among them to win feminine flavours. The life of the contemporary lords was as empty and shallow as the life of the ladies. The shallowness and superficiality of the time where also clear from the kind of gossip that went on at the court. Card parties where common, ombre was the favourite game among Lords and ladies, coffee drinking was another most important diversion of the time.

In The Rape Of The Lock we are given a satirical picture of judges and jury members and merchants. Besides this there are found innumerable references in the poem which are closed connected to contemporary 18th century England. For instance, references are made of Hyde Park Circus, The Mall, Rosamonda's Lake. The name of the well known 18th century astrology Partridge and Hampton court and many others this is how Pope has described the contemporary 18th century in his mock heroic epic.

Poetic satire might very properly be regarded as didactic poetry, for the object it has in view is the reformation of men and manners, and to this end the satirist takes the liberty of boldly censuring vice and vicious characters.

"The true end of satire is the amendment of vice by correction," says Dryden. And most people agree that satire is a "criticism of life, an exposure of human weaknesses, follies, absurdities and shortcomings." The satirist uses humor, wit, mockery, ridicule, innuendo and irony to achieve his goal, i.e., his moral end. His moral purpose gives him the standard or ideal with which he ridicules the deviations of society.

The Rape of the Lock is a satire on the aristocratic strata of the 18th-century society. In the very opening lines, the poet laughs at "little" men engaging in tasks so "bold", and at gentle ladies who are capable of such "mighty rage’’:

In Tasks so bold can Little Men engage,And in soft Bosoms dwell such mighty Rage?(L. 11-12)

The contrast between "tasks so bold" and "little men" and another between "soft bosoms" and "mighty rage" is very wittily constructed and cuts clown to size these vain people of Pope's time.

Juvenal and Horace are the two well-known satirists in verse of Roman literature. The former's satire is pointed, full of force and often savage. The fierce indignation of Juvenal's censure and ridicule stands comparison with that of Swift in English literature, only that the latter is a prose satirist. Horace's irony is more graceful and easy; he chides with a smile. His manner might be compared with that of Addison in the Spectator Papers.

Satire is a distinct element in Chaucer, and yet he cannot be called a satirist. There is no misanthropy or cynicism in him, and his heart is too full of the milk of human kindness to qualify him for the trade of a satirist.

In the Elizabethan Age, John Donne (1573-1631), John Marston (1575-1634), and Joseph Hall (1574-1656), wrote poetical satires; their work is lacking in vigor, but it makes up for it in scurrility and abuse.

In the seventeenth century, Dryden wrote a number of, satires: Political, Absalom and Achitophel, personal, Mac Flecknoe, religious, The Hind, and the Panther. In the succeeding period, Pope is the great master of verse satire. The Dunciad or The Progress of Dullness, in which most of the writers who had the misfortune to incur the enmity of Pope are pilloried, and some of his Epistles belong to this class of writing.

According to Richard Garnet, "the expression in adequate terms of the sense of amusement or disgust excited by the ridiculous or unseemly, provided that humor is a distinctly recognized element, and that the utterance is invested with literary form. Without humor satire is invective; without literary form, it is mere clownish jeering."

Function of Satire. The true objective of a good satire is moral. It amends the vices by castigation. The satirist, in the language of Dryden, "is no more an enemy to the offender than the physician to the patient when he prescribes harsh remedies to an inveterate disease."

In Dryden's "Mac Flecknoe", Flecknoe is in search of a successor to his throne of foolishness finds no one better than his son Shadwell (whom Dryden considers to be a poetaster and a fool) of whom he says,

Tis resolved, for nature pleads that heShould only rule who mot resembles me.Shadwell alone my perfect image bears,Mature in dullness from his tender years;Shadwell alone of all my sons is heWho stands confirmed in full stupidity.The rest to some faint meaning make pretence.But Shadwell never deviates into sense.

With such scathing ridicule no other poet would dare to write again, and Dryden has been completely successful in his mission. This is exactly the function of satire.

Pope's satire, too, functions in somewhat the same manner. In The Rape of the Lock when Lord Plume is requested by his lady-love to persuade Lord Petre to surrender the "precious hairs" of Belinda, he utters words, which are unsurpassed in their emptiness:

With earnest Eyes and round unthinking Face,He first the Snuff-box open'd, and then the Case,And thus broke out - 'My Lord, why, what the Devil?Z-ds! damn the Lock! 'fore Gad, you must be civil!Plague on 't ! 'tis past a Jest-nay; prithee, Pox!'Give her the Hair' he spoke and rapp'd his Box.(L. 593-598)

What a torrent of meaningless words!

Pope's Personal and Impersonal Satires. Satire predominates in the works of Pope. Even a cursory glance at his poetry reveals that the major part of it consists of satire or is satiric in spirit. The Rape of the Lock, The Dunciad, Moral Essays, Satires and Epistles of Horace Imitated are the best of his satires.

Pope wrote many satires against individuals, which were deadly and sharp and they are marked by bitterness and malice. Stop ford Brooke, while comparing Dryden and Pope as satirists, points out that Dryden's work is done in large outline. "It has relation not only to the man he is satirizing, but to the whole of human nature, Pope's satire is thin, it confines itself to person, it has no relation to the greater world beyond his clique, and its voice both sharp and querulous, rises sometimes to a shriek of feeble vacuity."

When Shadwell is called the "last great prophet of tautology" in Mac Flecknoe, Dryden is not only passing an adverse judgment on Shadwell alone but on the whole race of poetasters. Pope's range on the other hand, is somewhat limited. In The Rape of the Lock the whole panorama is limited to 18th-century aristocratic life. In the strange battle, fought between the fashionable belles and the vain beaux, the fall of Dapperwit and Sir Fopling is particularly demonstrative of the hollowness of the people of this age:

A Beau and Witling perished in the Throng,One dy'd in Metaphor, and one in Song.(L. 703-704)

And even the greatest of the great, the Queen herself is satirized to produce a truly comical and witty effect:

Here Thou, Great Anna! whom three Realms obey,Dost sometimes Counsel take - and sometimes Tea.(L. 297-298)

Even for the Queen, the taking of counsel and the taking of tea is the same trivial matter.

"The Rape of the Lock" As An Impersonal Satire. The satire in The Rape of the Lock is directed not against any individual, but against the follies and vanities in general of fashionable men and women. Pope started writing this poem with the object of conciliating two quarreling families but as the poem progressed, the poet forgot his original intention, and satirized female follies and vanities. Belinda is not Arabella Fermor; she is the type of the fashionable ladies of the time, and in her, the follies and frivolities of the whole sex are satirized.

And the Baron represents not Petre alone but typifies the aristocratic gentlemen of the age. The strange battle between the sexes shows what sort of people these were. Just one example will amply demonstrate the levity of these people and also show that the criticism was leveled not against any individual alone but against the whole gamut of the aristocratic vanguard:

But this bold Lord, with manly Strength indu'd,She with one Finger and a Thumb subdu'd:Just where the Breath of Life his Nostrils drew,A Change of Snuff the wily Virgin threw;(L. 723-726)

And these lines which come earlier:

When bold Sir Plilme had drawn Clarissa down,Chloe stept in, and kill'd him with a Frown;She smil'd to see the doughty Hero slain,But, at her Smile, the Beau reviv'd again.(L. 711-714)

The System of Justice and The Judge Satirised. Not only that, but the poet has also satirized the system of justice and the judges. At four in the afternoon, judges hurriedly sign the sentence so that they could have their dinner in time. This is their sense of responsibility:

Mean while, declining from the Noon of Day,The Sun obliquely shoots his burning Ray;The hungry Judges soon the Sentence sign,And Wretches hang that Jury-men may Dine;(L. 309-312)

Even the concept of friendship has been attacked. Friends are hollow and fickle. Belinda's friend Thalestris is as shallow as the age in which she lives. As soon as the reputation of Belinda is gone, she does not like to be called her friend, because it will be a disgrace to be known as her friend henceforth.

Thus, the poem is a delicate, playful, humorous, original, witty satire on the upper-class society of the eighteenth century. Though genial and gentle, it is at times deadly. It does not condemn like Swift; it exposes the follies with a light ridicule.

"The Rape of The Lock" as a Satire upon Feminine Frivolity. The poem is, in fact, a satire upon feminine frivolity. It continues the strain of mockery against hoops and patches and their wearers, which supplied Addison and his colleagues with the materials of so many Spectators. Even in Addison there is something which rather jars upon us. His persiflage is full of humor and kindness but underlying it there is a tone of superiority to women which is sometimes offensive; it is taken for granted that woman is a fool, or at least should be flattered if any man condescends to talk sense to her. With Pope, this tone becomes harsher, and the merciless satirist begins to show himself. In truth, Pope can be inimitably pungent but he can never be simply playful. Addison was too condescending with his pretty pupils; but under Pope's courtesy there lurks contempt, and his smile has a disagreeable likeness to a sneer. If Addison's manner sometimes suggests the brilliant wit, Pope's contempt has a keener edge from his resentment against fine ladies blinded to his genius by his personal deformity.

Even in his dedication, Pope with unconscious impertinence insults his heroine for her presumable ignorance of his critical jargon. His smart epigrams want but a slight change of tone to become satire. It is the same writer who begins an essay on women's characters by telling a woman that her sex is a compound of and communicates to her the pleasant truth that every woman is at heart a rake.

Matter too soft a lasting mask to bear;And best distinguished by black, brown, or fair.

Women, in short, are all frivolous beings, whose genuine interest is in love-making. The same sentiment is really implied in the more playful lines of The Rape of the Lock. The sylphs are warned by omens that some misfortune impends; but they don't know what:

Whether the Nymph shall break Diana's law,Or some frail China Jar receive a Flaw,Or stain her Honour or her new Brocade,Forget her Pray'rs or miss a Masquerade,Or lose her Heart or Necklace at a Ball;Or whether Heav'n has doom'd that Shock must fall.(L. 253-258)

We can understand that Miss Fermor would feel such raillery to be equivocal. It may be added that an equal want of delicacy is implied in the mock-heroic battle at the end, where the ladies are gifted with an excess of screaming power:

Restore the lock She cries, and all aroundRestore the lock the vaulted Roofs reboundNot fierce Othello in so loud a StrainRoar'd for the Handkerchief that caus'd his Pain.(L. 747-750)

Pope was inspired by a prevailing sentiment of contempt towards the whole female sex. The witty lines are read not with kind irony but as disagreeable sneers. If Miss Fermor was pleased, as she seems to have been with her reflection in the character of Belinda, she certainly gave countenance to what was evidently Pope's opinion. Perhaps the idle society-women of Pope's day deserved no higher estimate: but it is not to be supposed that the whole sex was dominated by puffs, powders, patches and billet-doux. It is fair to laugh at the lovers and lap-dogs, the devotion to Bohea and China vases: it is not fair to leave us with the impression that nothing higher was possible. But as Pope thought, it is not a poet's business to look beyond his age, the result may be accepted, because the poem undoubtedly strikes off a vivid picture of certain current fashions which were as ludicrous as they were transitory. The picture remains bright and entertaining because under similar conditions these fashions do arise from certain traits in female character which seem to be fundamental.

Conclusion. The poem is a reflection of this artificial and hollow life, painted with a humorous and delicate satire. It paints the idle life of the pleasure-seeking young men and women. It introduces us to a world of frivolity and fashion, which was busy with its pleasures. These pleasures were petty and frivolous - dressing, flirting, card playing, driving in Hyde Park, visiting theatres, writing love-letters, and so on and so forth. Their whole day's program seems to be nothing but a waste.

We see, here, Belinda sleeping on till noon and dreaming of young lovers and fashions of dress. Her lap dog Shock awakens her with a lick of his tongue. This is significant. She first reads love letters and then goes straight to her dressing or toilette table. Pope gives a very original and witty account of her toilet. So vain is she that dressing seems to be some religious rite or ceremony. He calls it 'the scared rites of Pride.' The number of cosmetics on the table, the whole procedure of preparing the toilette, etc., is a great satire on fashionable ladies of the times. Their dress is frivolous, their minds are sprightly and their hearts moving toy-shops which they sell now to John and then to David.

We see her, next going with a party of admirers, up the river Thames to Hampton Court palace and holding her Darbar there as if she were a queen. She smiles upon well-dressed fops that crowded round her. Then follows an account of the game of cards and of coffee drinking, leading to the catastrophe, the cutting of her lock of hair. He then describes the hypocritical fits of passion and battles for the severed lock of hair. 'Here is an epic of the frivolous'. Pope paints the vanity and shallowness of this life. Likewise, the poet also gives us an account of the frivolous young men. They run after ladies, now this, now that; they hang about their boxes in the theaters and their coaches in the Hyde Park. They display their hair in rings; give parties and invite people to balls. They are as insincere and hollow as the ladies whom they love.

Pope's satire is intellectual and full of wit and epigram. His picture of Addison as Atticus though unjust and prompted by malice, is a brilliant piece of satire. "As an intellectual observer and describer of personal weakness, Pope stands by himself in English verse." (Lowell).

SELECTED LITERARY CRITICISM ON THE TOPIC

Joseph Warton. It is judicious to open the poem by introducing the guardian-sylph warning Belinda against some secret impending danger. The account which Ariel gives of the nature, office and employment of these inhabitants of air, is finely fancied: into which several strokes of satire are thrown with great delicacy and address. The transformation of women of different tempers into different kinds of spirits cannot be too much applauded. The description of the toilette, which succeeds, is judiciously given in such magnificent terms as dignify the offices performed at it. Belinda's dressing is painted in as pompous a manner, as Achilles' arming. The canto first ends with a circumstance, artfully contrived to keep this beautiful machinery in the reader's eye: the busy sylphs surround their darling care.

Bonamy Dobree. The great increase in the size of the poem (revised version) was the result of Pope's decision to introduce the machinery of the classical epic; but instead of gods, he took the sylphs he had discovered in an esoteric work, "Le Comte de Gabalis," by Abbe de Villiers, and in doing so he contrived an enchanting iridescence. Yet this shimmering background served not only as a setting for good hard-hitting wit, social criticism, and a real philosophy subtly indicated by giving a sense of the fullness and richness of existence combined with a moral sense which put everything in its proper proportion.

Stopford Brooke. Dryden's satire relates not only to the man he is satirizing, but to the whole of human nature. Pope's satire is thin, it confines itself to person, it has no relation to the greater world beyond his clique, and its voice both sharp and querulous, rises sometimes to a shriek of feeble acuity.

Lowell. As an intellectual observer and describer of personal weaknesses, Pope stands by himself in English verse.

UNIVERSITY QUESTIONS

Pope is pre-eminently a satirist/ Discuss with illustrations.

Or

'The Rape of the Lock, is in fact, a satire upon feminine frivolity/ Discuss with illustrations.

Or

'The artificial tone of the age, the frivolous aspect of feminity is nowhere more exquisitely pictured than in The Rape of the Lock.' Elucidate.

Or

Discuss The Rape of the Lock as the satirical picture of aristocratic society.

Or

"The Rape of the Lock is enjoyable both as a mock-epic and as a satire on the affections and frivolity of the fashionable world." Discuss.

Or

Which aspect of men's life - the nature or the social - is the

object of Pope's satire in The Rape of the Lock. Illustrate your answer.

Or

Discuss The Rape of the Lock as a social satire.

Or

It is not possible to make great poetry out of satire. Discuss this statement with reference to The Rape of the Lock.

Or

Discuss. The Rape of the Lock as a satire on immoderate female pride.

Or

"A serious anatomy of 'polite' behavior which probes the ageless heart and pretenses of the sex war." Is this estimate of The Rape of the Lock