Also Read

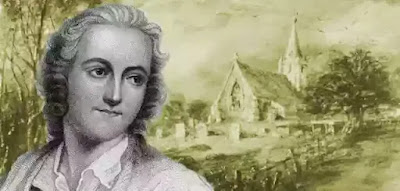

Thomas Gray (1716-1771) was born in London, the son of a money-scrivener, a kind of lawyer, who was in affluent circumstances. Gray, however, owed his education largely to the self-denial of his mother; he was educated at Eton and Cambridge, at the former of which places he met Horace Walpole. With Walpole he toured Italy and France; then, returning to the university, he took his degree, finally settling down to a life that was little more than an elegant futility. He was offered the Laureateship, but refused it (1757); he obtained a professorship at Cambridge, but he never lectured. He wrote a little, travelled a little; but he was a man of shrinking and fastidious tastes, unapt for the rough shocks of the world, and, fortunately for himself, able to withdraw beyond them.

His first poem was the Ode on a Distant Prospect of Eton College (1747), which contained gloomy moralizings on the approaching fate of those "little victims," the schoolboys. Then, after years or revision and excision, appeared the famous Elegy written in a Contry Churchyard (1751). This poem was, smooth and graceful; it contained familiar sentiments turned into admirable, quotable phrases, and so, while it was agreeably familiar, it was fresh enough to be attractive. Its popularity has been maintained to the present day. His Pindaric Odes (1757) were unsuccessful, being criticized for their obscurity. The Bard and The Progress of Poesy, the two Pindaric odes in the book, certainly require some elucidation, especially to readers not familiar with history and literature. At the first glance Gray's odes are seen to have all the odic splendour of diction; in fact, the adornment is so thickly applied that it can almost stand alone, like a robe stiff with gems and gold lace. Yet the poems have energy and dignity. Johnson, who had a distaste for both the character and the work of Gray, cavills at the work, saying that it has a strutting dignity. "He is tall by walking on tiptoe. His art and his struggle are too visible."

The prose work of Gray is notable. It consists partly of letters written during his travels, describing the scenes he visits. In them he shows vigour of style, and a sharp eye and a generous admiration for the real beauties of nature. His descriptions, such as those of the Lake District, are quite admirable, and well in advance of the general taste of his age. In spite of its slender bulk, Gray's achievement both in prose and verse is of great importance. He explored the origins of romance in the early Norse and Celtic legends; his sympathies with the poor and oppressed were genuine and emphatically expressed; and his treatment of nature was a great improvement upon that of his predecessors.

Johnson's final estimate of Gray is not unfair, and we can leave the poet with it: "His mind had a large grasp; his curiosity was unlimited, and his judgment cultivated; he was a man likely to love much where he loved at all, but he was fastidious and hard to please.