Also Read

Summary and Analysis

Summary :

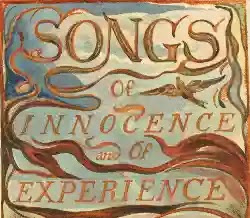

Blake Songs of Innocence (as well as Experience) is collection of poems united all the grand combinations of art and mind, poetry, music and painting, copying none, but breathing spirit and life into his work and shaping forms from the world of his creative and sportive imagination. His work is the fanciful product of rich imagination, drawing, colouring, poetry which he united to form a beautiful whole. The poems in the section of Innocence are particularly remarkable for the transparent depth of thought which constitutes true simplicity - they give us glimpse of all that is holy in the childhood of the world and the individual they abound in the sweetest touches of that pastoral life by which the Golden Age may still be visibly represented to the Iron Age. It was when Blake was a little over thirty that he collected and published one of his sweetest and most original works. the Songs of Innocence, engraving the poems in a unique way with picturesque designs on copper. These copper plates are somewhat crude. deep-cut casts from engraved wood blocks. He managed to get these designs remain in relief by some technical and chemical means. These he printed with his own hands, in various tones of brown, blue and grey tinting them afterwards by hand into a sort of rainbow-coloured page, in which the thrilling music of the verse and the gentle bedazzlement of the lines and colours intermingle.

The General Theme :

In Songs of Innocence Blake deals with the pure innocence of children and the heavenly, secure and gleeful pastoral world of sport and merry-making. In this section we see the children enjoying unbridled freedom, they play until they are satisfied, they speak to animals like lambs and sheep which are as innocent as themselves. It is a heaven that lies about their infancy. The unstained world of innocence also provides them guardian angels for ensuring their security. In this section Blake is not exclusively unconcerned with the evil practices in the society against children. The litle black boy and the chimney sweeper lament their lots. But what differentiates them from the world of Experience is that, at the end of all such poems that give expression to the hostility of the society Blake brings the children out of the fold of this vicious circle and restores them to the heavenly abode of God. In this section Blake also brings in his theory of God-God as child and lamb. Thus God, lamb and child form a trinity. He fills the scenes of Innocence with angels who talk to children and mingle with them. In Innocence we hear the wren-like warblings echoing in the green fields and gardens. The pastoral settings is sunny, full of flying and warbling birds and ringing sonorous bells. The problem of these songs lies in their peculiar naivety. This is not the simplicity of childhood, of incomplete experience; this simplicity has its origin in no experience at all. Blake's condemnation of the perishing Vegetable Memory as a substitute for inspiration, and his preference of the 'Eternal Image' to the actual object, are both relevant here. The images of the Songs of Innocence are seen in a vision. within a moment, a Pulsation of Artery.

Symbols :

In Songs of Innocence Blake weaves the texture of the poems with the warp and woof of symbolism and pictorial beauty. In his poems the lamb is a symbol of 'The Lamb' of God that taketh away the sin of the world. 'The Echoing Green' is not merely the depiction of a merry day: it is a symbolic presentation of the "Day of Innocence" from sunrise to sunset. "Infant Joy', 'The Little Black Boy' and "Laughing Songs' symbolize the three ages of Innocence infancy, childhood and youth. 'A Cradle Song', 'Nurse's Song' and 'Holy Thursday' are symbolic of the same three ages of man, this time in relation to society, and the remaining poems, which image the human soul in its quest of self-realization, are all of even deeper symbolic import. Reading them in the categorical order in which Blake once decided they should be arranged, we pass through consecutive stages of development from infancy to self-consciousness.

The use of symbolism in Blake's poems is not to be neglected. Without symbols, these poems could not have been rendered. Blake's state of innocence set forth in symbols of pastoral life akin to those of the twenty-third psalm seems at first sight to have something in common with what Vaughan, Traherne and Wordsworth say in their different ways about the vision of childhood which is st in later life. For him childhood is both itself and a symbol of a state of soul which may exist in maturity. His subject is the childlike vision of existence. For him all human beings are in some sense, and at some time, the children of a di vine father. (What he describes are not actual events as ordinary men see and understand them, but spiritual events which have to be stated symbolically in order that they may be intelligible. In the songs of Innocence Blake's symbols are largely drawn from the Bible, and since he makes use of such familiar figures as the Good Shepherd and the Lamb of God, there is not much difficulty in seeing what he means. Indeed some poems of innocence are fully understandable only by reference to symbols which Blake uses in his prophetic books; and since the meaning of most symbols tends to be inconstant, there is always a danger that we may make his meaning more emphatic or more exact than it is, especially since as Blake grew older, he developed his symbols and, by placing them in precise contexts, gave them a greater definiteness.

Religious Elements in Innocence :

In the Songs of Innocence the symbols convey a special kind of existence or state of soul. In this state human beings have the same kind of security and assurance as belongs to lambs under a wise shepherd or to children with loving parents. Nor is it untrue to say that both the shepherd and the father of Blake's poems is God. It is He who is Himself a lamb and becomes a little child, who watches over sleeping children and gives his love to chimney sweepers and little black boys. In the fatherhood of God, Blake's characters have equal rights and privileges. But by it he means not quite what the orthodox Christians do. Blake, despite his deeply religious nature, did not believe that God exists apart from man, but says expressly:

Man is all Imagination-God is Man and exists in us and we in Him

.....imagination or the Human Eternal Body inEvery Man.... Imagination is the Divine Body in Every Man.

For Blake, God and the imagination are one; that is God is the creative and spiritual power in man, and apart from man the idea of God has no meaning When Blake speaks of the divine it is with reference to this power and not to any external or independent godhead. So when his songs tell of God's love and care we ought to think of them as qualities which men themselves display and in so doing realize their full divine nature.

Sweet and pure though the 'Songs of Innocence' are, they do not possess or need the compelling passion of the 'Songs of Expericnce.' In dealing with innocence Blake seems deliberately to have set his tone in a quiet key to show what innocence really means in his full scheme of spiritual development. He was careful to exclude from the first part of his book anything which might sound a disturbing note or suggest that Innoccnce is anything but happy.

Faults and Merits :

Blake, when he began to write the Songs had a clear perspective of the Golden Age in his mind. When we go through his works, transient glimpses of our past childhood unfold before our eyes and we are brought to face a new spiritual light. Objects which are familiar to us are treated in a different light. ln their unfamiliar, transfigured aspects, simple expressions hide deep meanings organized as types and antitypes. In his works there are many irregularities, such as lapse of grammar and metrical improprieties: but the sweet melody and eloquent rhythm are remarkable. Their visible spontaneity and rare charm are comparable to the old English ballads. The form of these poems is a transparent medium of the spiritual thought, not an opaque body of philosophical jargon.

Some Typical Specimens from Innocence :

Closely related to the necessity of reading each song in terms of its state is the vital importance of point of view. Often it is unobtrusive, but many a time upon a correct determination of speaker and perspective depends a faithful interpretation of the poem. Blake himself suggests this by his organization of the songs into series, Innocence introduced and sung by the piper, Experience by the Bard. Superficially there seems to be little to distinguish one from the other since the piper clearly exhibits imaginative vision and the Bard Present. Past, and Future sees.' Yet for each. the past, present and future are different. For the piper the past can only be the primal unity, for the present is innocence and the immediate future is experience; for the Bard the past is innocence, the present experience, the future a higher innocence. It is natural, then, that the piper's point of view is prevailingly happy, he is conscious of the child's essential divinity and assured of his present protection. But into that joyous context the elements of experience constantly insinuate themselves so that the note of sorrow is never completely absent from the piper's pipe.

One of the other specimens in which we see the hillside greenery of innocence is The Echoing Green. Here the scene and the day-night cycle and the images of animated nature corresponding with human activity parallel Spenser's Epithalamion. Both 'Introduction' and 'The Echoing Green' describe nature as a part of the whole setting.

The Litle Black Boy : The Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade was formed in 1787 and many artists and writers were involved in this movement. Blake too opposed slavery, but the plea of this poem is more fundamentally against doctrines of racial and religious superiority. Immediate targets may have been Watts's lyrics Praise for Birth and Education in a Christian Land and Praise for the Gospel, in both of which a little English boy thanks God for letting him be born a Christian and pities the heathen. Blake's, humanity and philanthropism are reflected in 'The Little Black Boy.' Reminiscences of Watts are again brought in the lines: "And we are put..... grove" (Stanza 4, lines 13 to 16). Watts's Grace Shining and Nature Fainting' (Horae Lyricae, 1709) gives us the following lines of the same idea: "Nor is my soul refined enough / To bear the beaming of his love, / And feel his warmer smiles. / When shall I rest this drooping head / I love, I love the sun, and yet I want the shade!" In his poem (Stanza 4, Lines 15 to 16) Blake compares the human body to a cloud and this comparison can be traced to Dante's 'Purgatory' or (Ch. XX VIII L.90). Again in the last stanza the little black boy says "I shade him from the heat....love me." The two boys will be 'free' of their bodies yet one is still darker, one whiter and needing assistance. Why? The paradox is adumbrated by Job: though after my skin worms destroy this body, yet in my flesh shall I see God".

The Chimney Sweeper : This poem can be read in two contrary ways. One way is to see it as an indictment of a society which enslaves children both physically and spiritually, promising heaven hereafter in exchange for obedient suffering here; its conclusion in favour of 'duty' is bitterly ironic as in 'Answer to the Parson'. Blake writes:

Why of the sheep do you not learn peaceBecause I don't want you to shear my fleece.

The other way (the opposite) in which we can read this poem is as a celebration of the boy's imagination. Read in this way, the concluding line of the poem is positive; the happiness and warmth are not delusive but real, and 'duty' means seeing and feeling the delightful reality of spiritual life. This is further clarified and emphasized in Blake's letter to Hayley in which he says now I have lamented over the dead horse let me laugh and be merry.... for as Man liveth not by bread alone I shall live altho 'I should want bread - nothing is necessary to me but to do my Duty and to rejoice in the exceeding joy that is always poured on my Spirit.

Alexander Gilchrist says: "For a nobler depth of religious beauty, with accordant grandeur of sentiment and language, I know no parallel or hint elsewhere of such a poem as 'The Little Black Boy'. We may read these poems again and again and they continue fresh as at first. There is something unsating in them, a perfume as of growing violet, which renews itself as fast as it is inhaled. 'The Chimney Sweeper' still calls for special notice. This and 'Holy Thursday' are remarkable as an anticipation of the daring choice of a homely subject, of the yet more daringly familiar manner, may, of the very metre and trick of style adopted by Wordsworth in a portion of those memorable 'experiments in poetry' - the Lyrical Ballads...The little sweep's dream has the spiritual touch peculiar to Blake's hand."

Other Poems :

Except in some of the 'wren-like warblings' of Innocence almost all the greatest works are harmonies, a theme with a deeper and sometimes several deeper meanings reverberating below, or perhaps one should say within. 'The Blossom' for instance is a pretty little song of the garden on the surface, but it is also (fairly obviously) a lullaby or cradle song. Closely examined it turns to be a unique and exquisite love-song, conveyed in symbols and closely associated with the exquisite inner theme of 'Infant Joy'. Deepest of all, it reveals itself in conjunction with the illustration as an essay on bodily love, its beauty and its course in human life. not omitting also its expression in Art. All his is condensed into forty-four words, including the title (twenty-seven if we omit repetitions) and a few simple lines of decoration - the work certainly of a very great master and craftsman, but a master of childlike words, of unconventional but essentially childlike ideas; of a childlike absence of' reticence, of childlike and joyous originality, and of a childlike indifference to being understood. Only in a few of those faultless fragments of childish rhyme which float without name or form upon the memories of men shall we find such pure clear cadence of verse, such rapid ring and flow of lyrical laughter, such sweet and direct choice of the just word and figure, such an impeccable simplicity: nowhere but here such a tender wisdom of holiness, such a light and perfume of innocence. Nothing like this was ever written on that text of the lion and the lamb; no such heaven of sinless animal life was ever conceived so intensely and sweetly: "And there the lion's.... weep." (Iast two stanzas of the poem 'Night' - Lines 33 to 48).

The leap and fall of the verse is so perfect as to make it a fit garment and covering for the profound tenderness of faith and soft strength of innocent impulses embodied in it, but the whole of the hymn of 'Night' is beautiful, being perhaps one of the two poems of loftiest loveliness among all the songs of innocence.

Conclusion :

Blake's poems in Songs of Innocence and Experience allude to the Bible in a large scale. He can also be noted as indebted to Watts in many aspects of his poems. For instance 'A Cradle Song' is in part a reaction to Watt's metrically similar 'Cradle Hymn' where the mother congratulates her infant on being materially better off than the infant Jesus : How much better thou'rt attended / Than the Son of God could be...Here's no ox anear thy bed", and so on. Blake's mother sings of spiritual rather than material grace, and perceives the closeness of infant and Creator rather than the distinction. Blake's "A Dream and Watts's song The Ant or Emmet are metrically similar. As for Blake's indebtedness to the Bible we can easily quote many examples. The 'life's river' of 'Night' refers to the sentence of Revelation running : And he showed me a pure river of water of life, clear as crystal, proceeding out of the throne of God and of the Lamb. Again, in 'Infant Joy' the repetition of I am (Lines 2 to 50 in connection with the query "what shall call thee? Suggests Moses first encounter with the God who identifies Himself as. "I AM" By implication the infant is divine and divinity is 'joy'. In 'On Another's Sorrow', the 22nd line in the sixth stanza refers to the words of Revelation and God shall wipe away all tears from their eyes.