Also Read

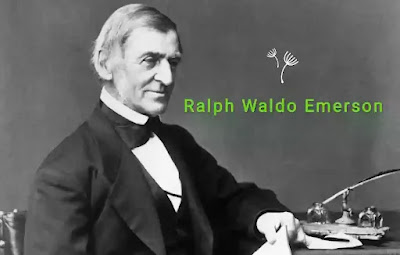

Ralph Waldo Emerson, (1803-1882) the most distinguished of New England transcendentalists, came from a family of clergy. Peter Bulkeley, his ancestor, was the first pastor of Concord in 1635. William Emerson, his grandfather, was pastor in Concord at the opening of the Revolutionary War and witnessed the fight of Concord Bridge from the window of the Old Manse, that famous house which he had built and which Hawthorne afterwards occupied. By that Bridge there stands a monument, commemorating the heroic services of the men who there made the world-famous stand for freedom. On the base of this monument are Ralph Waldo Emerson's lines:—

"By the rude bridge that arched the flood,Their flag to April's breeze unfurled,Here once the embattled farmers stood,And fired the shot heard round the world."

Ralph Waldo Emerson was born in Boston in 1803. His father, who was pastor of the First Church in Boston, died when Ralph Waldo was eight years old, leaving in poverty a widow with six children under ten years of age. His church promptly voted to pay his widow five hundred dollars a year, for seven years, but even with this help the family was so poor that in cold weather it was noticed that Ralph and his brother went to school on alternate days. The boys divined the reason, and were cruel enough to call out, "Whose turn is it to wear the coat to-day?" But the mother struggled heroically with poverty, and gave her sons a good education. Ralph Waldo entered Harvard in 1817. He saved the cost of his lodging by being appointed "President's Freshman," as the official message bearer was called, and earned most of his board by waiting on the table at the college Commons.

Emerson was descended from such a long line of clergymen that it was natural for him to decide to be a minister. After graduating at Harvard and taking a course in theology, he received a call from Cotton Mather's church and preached there for a short time; but he soon resigned because he could not conscientiously conform to some of the customs of the church. Although he occasionally occupied pulpits for a few years after this, the greater part of his time for the rest of his life was spent in writing and lecturing.

When he was temporarily preaching in Concord, New Hampshire, in 1827, he met Miss Ellen Tucker, then sixteen years old. This meeting was for two reasons a noteworthy event in his life. In the first place, her inspiration aided in the development of his poetical powers. He seemed to hear the children of Nature say to her:—

"Thou shalt command us all,—April's cowslip, summer's clover,To the gentian in the fall,Blue-eyed pet of blue-eyed lover."

Ralph Waldo Emerson, the towering figure of his era, had a strong religious sense of mission. Born us the son of William Emerson, the Minster of First Utilitarian Church of the native of Boston. He completed his education at Harvard and became a Minister in 1829. In 1832 shortly after the death of his first wife, he resigned from the ministry and sailed to Europe. His mind was disturbed by the personal grief and religious confusion. There, he met S.T. Coleridge, William Wordsworth and Thomas Carlyle.

In 1835, Emerson married Lydia Jackson and moved to Concord, Massachusetts where his ancestors first settled in the New World. There, he made the group of ‘transcendentalists’ like Brownson Alcott, Margaret Fuller, H.D. Thoreau and Nathanial Hawthorne. “Nature” was his first book published in 1836. ‘The American Scholar’ (1837) came out as he attended national and cultural questions in it as he failed to appeal to the European audience by his unimpressive lectures. Although many complained to him of subverting the Christian religion, he explained that for him “to be a good minister, it was necessary to leave the church.” The address delivered in 1838 at Harvard Divinity School, his alma mater, made him unwelcome at Harvard for the next 30 years. In it, Emerson accused the church of acting “as if God were dead” and of emphasizing dogma while stifling the spirit. His philosophy has been called ‘contradictory’ and true that he consciously avoided building a logical intellectual system because such a rational system would have negated his romantic belief in intuition and flexibility. Two volumes of essays were published in 1941 and 1844. His first collection of poems got published in 1847 and later with May-Day and Other Poems (1867). Again, in 1847 he moved to England and lectured at Oxford and London. His lectures were published under the titles Representative Men (1850) and English Traits (1856). I Hiring this period, he became deeply interested in the issue of slavery and saw the Abolition as a matter of paramount importance.

In his essay “Self-Reliance,” Emerson remarks: “A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.” Yet he is remarkably consistent in his call for the birth of “American Individualism” inspired by nature. Most of his major ideas - the need for a new national vision, the use of personal experience, the doctrine of compensation - are suggested in his first publication, “Nature” (1836). His essay opens: “Our age is retrospective. It builds the sepulchers of the fathers. It writes biographies, histories, criticism. The foregoing generations beheld God and nature face to face; we, through their eyes. Why should not we also enjoy an original relation to the universe? Why should not we have poetry of insight and not of tradition, and a religion by revelation to us, and not the history of theirs? Embosomed for a season in nature, whose floods of life stream around and through us, and invite us by the powers they supply, to action proportioned to nature, why should we grope among the dry bones of the past. The sun shines today also. There is more wool and flax in the fields. There are new lands, new men, and new thoughts. Let us demand our own works and laws and worship.”

Emerson loved Montaigne, the French essayist and aphoristic genius of the 16th century. He once told Bronson Alcott that he always wanted to write a book like Montaigne’s, “full of fun, poetry, business, divinity, philosophy, anecdotes and smut.” He rather regretted that Alcott’s abstract style omitted “the light that shines on a man’s hat, in a child’s spoon.” The spiritual vision and practical, aphoristic expression make Emerson exhilarating. One of the Concord Transcendentalists aptly compared listening to him with “going to heaven in a swing.” Much of his spiritual insight comes from his readings in Eastern religions, especially Hinduism, Confucianism, and Islamic Sufism. For example, his poem “Brahma” relies on Hindu sources to assert a cosmic order beyond the limited perception of the mortals. The poem “Brahma’ runs as:” If the red slayer think he slay/ Or the slain think he is slain/, They know not well the subtle ways /I keep, and pass, and turn again./ Far or forgot to me is near/ Shadow and sunlight are the same; /the vanished gods to me appear/; And one of me are shame and fame. They reckon ill who leave me out;/ When me they fly, I am the wings; /I am the doubter and the doubt/, And I the hymn the Brahmin sings/ The strong gods pine for my abode,/ And pine in vain the sacred Seven, /But thou, meek lover of the good! /Find me, and turn thy back on heaven.”

This poem, published in the first number of the Atlantic Monthly Magazine (1857), confused readers unfamiliar with Lord Brahma, the great Hindu god, the eternal and infinite soul of the universe. Emerson had this advice for his readers: “Tell them to say Jehovah instead of Brahma.” Matthew Arnold, the great British poet-critic, said that the most important writings in English in the 19th century had been Wordsworth’s poems and Emerson’s essays. A great prose-poet, Emerson influenced a long line of American poets, including Walt Whitman, Emily Dickinson, Edwin Arlington Robinson, Wallace Stevens, Hart Crane, and Robert Frost. Also he is credited with influencing the philosophies of John Dewey, George Santayana, Friedrich Nietzsche, and William James.

ELLEN TUCKER

His verses tell how the flower and leaf and berry and rosebud ripening into rose had seemed to copy her. He married her in 1829 and wrote the magnificent prophecy of their future happiness in the poem beginning:—

"And Ellen, when the graybeard years,"

A poem which he could not bear to have published in his lifetime, for Mrs. Emerson lived but a few years after their marriage. In the second place, in addition to stimulating his poetical activity, his wife's help did not end with her death; for she left him a yearly income of twelve hundred dollars, without which he might never have secured the leisure necessary to enable him "to live in all the faculties of his soul" and to become famous in American literature.

In the fall of 1833 he sailed for Europe, going by way of the Mediterranean. Returning by way of England, he met Coleridge, Wordsworth, and Carlyle, whose influence he had already felt. His visit to Carlyle led to a lifelong friendship. Emerson helped to bring out an American edition of the Sartor Resartus (1836) before it was published in England.

EMERSON'S STUDY

After returning from Europe, Emerson permanently settled at Concord, Massachusetts, the most famous literary town of its size in the United States. The appreciation of the Concord people for their home is shown by the naive story, told by a member of Emerson's family, of a fellow townsman who read of the rapidly rising price of building lots in Chicago, and remarked, "Can't hardly believe that any lands can be worth so much money, so far off." After Henry D. Thoreau had received a medal at school for proficiency in geography, he went home and asked his mother if Boston was located in Concord. It was to Concord that Emerson brought his second wife, Lidian Jackson Emerson, whom he married in 1835. In Concord he wrote his most famous Essays, and from there he set out on his various lecturing tours. There he could talk daily to celebrities like Nathaniel Hawthorne, Henry Thoreau, and Bronson Alcott. Louisa May Alcott relates that when eight years old she was sent to the Emerson home to inquire about the health of his oldest son, a boy of five. Emerson answered her knock, and replied, "Child, he is dead!" Years later she wrote, "I never have forgotten the anguish that made a familiar face so tragical, and gave those few words more pathos than the sweet lamentation of the Threnody" Like Milton and Tennyson, Emerson voiced his grief in an elegy, to which he gave the title Threnody. In this poem the great teacher of optimism wrote:—

"For this losing is true dying;This is lordly man's down-lying,This his slow but sure reclining,Star by star his world resigning."

Aside from domestic incidents, his life at Concord was uneventful. As he was by nature averse to contests, he never took an extreme part in the antislavery movement, although he voiced his feelings against slavery, even giving antislavery lectures, when he thought the occasion required such action. His gentleness and tenderness were inborn qualities. Oliver Wendell Holmes said that Emerson removed men's "idols from their pedestals so tenderly that it seemed like an act of worship."

He widened his influence by substituting the platform for the pulpit, and year after year he enlarged his circle of hearers. He lectured in New England, the South, and the West. Sometimes these lecture tours kept him away from home the entire winter. In 1847 he lectured in England and Scotland. He visited Carlyle again, and for four days listened to "the great and constant stream" of his talk. On this second trip abroad, Emerson met men like De Quincey, Macaulay, Thackeray, and Tennyson. Emerson gained such fame in the mother country that, long after he had returned, he was nominated for the Lord Rectorship of Glasgow University and received five hundred votes against seven hundred for Disraeli, one of England's best known statesmen.

Something of his character and personality may be learned from the accounts of contemporary writers. James Russell Lowell, who used to go again and again to hear him, even when the subject was familiar, said, "We do not go to hear what Emerson says so much as to hear Emerson." Hawthorne wrote, "It was good to meet him in the wood paths or sometimes in our avenue with that pure intellectual gleam diffusing about his presence like the garment of a shining one." Carlyle speaks of seeing him "vanish like an angel" from his lonely Scotch home.

Emerson died in 1882 and was buried near Hawthorne, in Sleepy Hollow cemetery at Concord, on the "hilltop hearsed with pines." Years before he had said, "I have scarce a daydream on which the breath of the pines has not blown and their shadow waved." The pines divide with an unhewn granite boulder the honor of being his monument.

EARLY PROSE.—Before he was thirty-five, Emerson had produced some prose which, so far as America is concerned, might be considered epoch-making in two respects: (1) in a new philosophy of nature, not new to the world, but new in the works of our authors and fraught with new inspiration to Americans; and (2) in a new doctrine of self-reliance and intellectual independence for the New World.

EMERSON'S GRAVE, CONCORD

In 1836 he published a small volume entitled Nature, containing fewer than a hundred printed pages, but giving in embryo almost all the peculiar, idealistic philosophy that he afterwards elaborated. By "Nature" he sometimes means everything that is not his own soul, but he also uses the word in its common significance, and talks of the beauty in cloud, river, forest, and flower. Although Nature is written in prose, it is evident that the author is a poet. He says:—

"How does Nature deify us with a few and cheap elements! Give me health and a day, and I will make the pomp of emperors ridiculous. The dawn is my Assyria; the sunset and moonrise my Paphos, and unimaginable realms of faerie; broad noon shall be my England of the senses and the understanding; the night shall be my Germany of mystic philosophy and dreams."

Emerson tried to make men feel that the beauty of the universe is the property of every individual, but that the many divest themselves of their heritage. When he undertook to tell Americans how to secure a warranty deed to the beauties of nature, he specially emphasized the moral element in the process. The student who fails to perceive that Emerson is one of the great moral teachers has studied him to little purpose. To him all the processes of nature "hint or thunder to man the laws of right and wrong, and echo the Ten Commandments." In Nature, he says:—

"All things with which we deal, preach to us. What is a farm but a mute gospel? The chaff and the wheat, weeds and plants, blight, rain, insects, sun,—it is a sacred emblem from the first furrow of spring to the last stack which the snow of winter overtakes in the fields."

In Nature, Emerson sets forth his idealistic philosophy. "Idealism sees the world in God" is with him an axiom. This philosophy seems to him to free human beings from the tyranny of materialism, to enable them to use matter as a mere symbol in the solution of the soul's problems, and to make the world conformable to thought. His famous sentence in this connection is, "The sensual man conforms thoughts to things; the poet conforms things to his thoughts."

In The American Scholar, an address delivered at Cambridge in 1837, Emerson announced what Oliver Wendell Holmes calls "our intellectual Declaration of Independence." Tocqueville, a gifted Frenchman who visited America in 1831, wrote: "I know no country in which there is so little independence of opinion and freedom of discussion as in America…. If great writers have not existed in America, the reason is very simply given in the fact that there can be no literary genius without freedom of opinion, and freedom of opinion does not exist in America." Harriet Martineau, an English woman, who came to America in 1830, thought that the subservience to opinion in and around Boston amounted to a sort of mania. We have already seen how Cooper in his early days deferred to English taste, and how Andrew Jackson in his rough way proved something of a corrective.

Emerson proceeded to deal such subserviency a staggering blow. He denounced this "timid, imitative, tame spirit," emphasized the new importance given to the single person, and asked, "Is it not the chief disgrace in the world not to be a unit;—not to be reckoned one character;—not to yield that peculiar fruit which each man was created to bear; but to be reckoned in the gross, in the hundred, or the thousand, of the party, the section, to which we belong, and our opinion predicted geographically, as the North, or the South?" Then followed his famous declaration to Americans, "We will walk on our own feet; we will work with our own hands; we will speak our own minds."

No American author has done more to exalt the individual, to inspire him to act according to his own intuitions and to mold the world by his own will. Young Americans especially listened to his call, "O friend, never strike sail to a fear! Come into port greatly, or sail with God the seas."

ESSAYS.—The bulk of Emerson's work consists of essays, made up in large part from lectures. In 1841 he published a volume, known as Essays, First Series, and in 1844, another volume, called Essays, Second Series. Other volumes followed from time to time, such as Miscellanies (1849), Representative Men (1850), English Traits (1856), The Conduct of Life (1860), Society and Solitude (1870). While the First Series of these Essays is the most popular, one may find profitable reading and even inspiring passages scattered through almost all of his works, which continued to appear for more than forty years.

When we examine his Essays, First Series, we find that the volume is composed of short essays on such subjects as History, Self-Reliance, Friendship, Heroism, and the Over-Soul. If we choose to read Self-Reliance, one of his most typical essays, we shall find that the sentences, or the clauses which take the place of sentences, are short, vigorous, and intended to reach the attention through the ear. For instance, he says in this essay:—

"There is a time in every man's education when he arrives at the conviction that envy is ignorance; that imitation is suicide; that he must take himself for better, for worse, as his portion."

Before we have finished Self-Reliance, he has made us feel that, with the exercise of self-trust, new powers will appear; that a man should not postpone his life, but live now; that a man is weak if he expects aid from others; that discontent is want of self-reliance.

We pick up another volume of essays, Society and Solitude, and wonder whether we shall read Success, or Books, or Civilization, or any one of nine others. While we are turning the pages, we see this sentence:—

"Hitch your wagon to a star,"and we decide to read Civilization.

"Now that is the wisdom of a man, in every instance of his labor, to hitch his wagon to a star, and see his chore done by the gods themselves. … We cannot bring the heavenly powers to us, but, if we will only choose our jobs in directions in which they travel, they will undertake them with the greatest pleasure…. Let us not lie and steal. No god will help. We shall find all their teams going the other way."

The youth is to be pitied if this does not quicken his determination to choose his work in the direction in which the aiding forces of the universe are traveling.

Some of Emerson's best social philosophy may be found in the essay, Considerations by the Way, published in the volume called The Conduct of Life. His English Traits records in a vigorous, interesting, common-sense way his impressions from his travels in the mother country. The English find in this volume some famous sentences, which they love to quote, such as,—

"That which lures a solitary American in the woods with the wish to see England, is the moral peculiarity of the Saxon race,—its commanding sense of right and wrong,—the love and devotion to that,—this is the imperial trait which arms them with the sceptre of the globe."

POETRY.—Emerson's verse is noteworthy for its exposition (1) of nature and (2) of his transcendental philosophy. He produced a comparatively small amount of poetry, but much more than he is popularly supposed to have written. Some of his verse is of a high degree of excellence; in fact, his nature poetry deserves to be ranked with the best that America has produced. Like Bryant, Emerson loves the forest. He says:—

"I go to the god of the woodTo fetch his word to men."

In The Poet, we see how great he thought the poet's debt to communion with nature:—

"The gods talk in the breath of the woods,

They talk in the shaken pine,

And fill the long reach of the old seashore

With dialogue divine;

And the poet who overhears

Some random word they say

Is the fated man of men

Whom the ages must obey."

Hawthorne saw Emerson one August day, wandering in Sleepy Hollow near Concord, and wrote, "He appeared to have had a pleasant time; for he said there were Muses in the woods to-day and whispers to be heard in the breezes." When Emerson was twenty-four years old, he wrote the following lines, which show the new feeling of mystic companionship with nature:—

"These trees and stones are audible to me,These idle flowers, that tremble in the wind,I understand their faery syllables."

His verses make us feel how nature enriches human life, increases its joys, and lessens its sorrows. What modern lover of nature has voiced a more heartfelt, unaffected appreciation of her ministrations than may be found in these lines from Emerson's Musketaquid?—

"All my hurts

My garden spade can heal. A woodland walk,

A quest of river grapes, a mocking thrush,

A wild rose or rock-loving columbine,

Salve my worst wounds."

From reading his best nature poem, Woodnotes, first published in The Dial, an appreciative person may find it easy to become

"Lover of all things alive,Wonderer at all he meets,"

To feel that in the presence of nature, every day is the best day of the year, and possibly even to sing with Emerson of any spring or summer day:—

"'Twas one of the charmed days

When the genius of God doth flow;

The wind may alter twenty ways,

A tempest cannot blow;

It may blow north, it still is warm;

Or south, it still is clear;

Or east, it smells like a clover farm;

Or west, no thunder fear."

All who love nature or who wish to become interested in her should read at least his Woodnotes, The Humble Bee, The Rhodora, Each and All, The Snow Storm, and To Ellen at the South.

Some of his philosophy may be found in poems like The Problem (1839), The Sphinx (1841), and Brahma (1857). The immanence of God in everything, in the sculptor's hand, for instance, is well expressed in The Problem:—

"The hand that rounded Peter's dome

And groined the aisles of Christian Rome

Wrought in a sad sincerity;

Himself from God he could not free;

He builded better than he knew;—

The conscious stone to beauty grew."

The Sphinx thus expresses one of Emerson's favorite thoughts:—

"To vision profounder,

Man's spirit must dive,"

And concludes with the Sphinx's thought-provoking statement:-

"Who telleth one of my meanings,

Is master of all I am."

This line in Brahma:—

"I am the doubter and the doubt,"

Shows his belief in the unity of all things, his conviction that all existence and action result from one underlying force. His own personal philosophy, that which actuated him in dealing with his fellow-men, is expressed in the following lines, which are worthy a place in the active memory of every American:—

"Life is too short to waste

In critic peep or cynic bark,

Quarrel or reprimand:

'Twill soon be dark."

While we are enjoying his poetry, we feel its limitations. Having slight ear for music, he often wrote halting lines. Sometimes his poetic flight is marked by too sudden a descent, but we shall often find in his verse rare jewels, such as:—

"When Duty whispers low, 'Thou must,'

The youth replies, 'I can.'"

These lines seemed to Oliver Wendell Holmes, the moment he saw them, as if they had been "carved on marble for a thousand years." Emerson's poetry does not pulsate with warm human feeling, but it "follows the shining trail of the ethereal," the ideal, and the eternal. His prose overshadows his poetry, but no one without natural poetical ability of a high order could have written the lines:—

"O tenderly the haughty day

Fills his blue urn with fire,"

or even have seen

"The frolic architecture of the snow."

GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS.—The central aim of Emerson's writing is moral development. He is America's greatest ethical teacher. He thus voices his fixed belief:—

"A breath of will blows eternally through the universe of souls in the direction of the Right and Necessary."

This belief gives rise to his remarkable optimism for the future, to his conviction that evil is but a stepping stone to good.

In a material age he is the great apostle of the spiritual. "Will you not tolerate," he asks, "one or two solitary voices in the land, speaking for thoughts not marketable or perishable?" To him "mind is the only reality," and his great man is never the one who can merely alter matter, but who can change our state of mind. He believed in reaching truth, guided by intuition. He would not argue to maintain his positions. He said that he did not know what argument signified with reference to a thought. To him a thought was just as natural a product as a rose and did not need argument to prove or justify its existence. Much of his work is tinged with Plato's philosophy.

Of all American writers, he is the most inspiring teacher of the young. One of his chief objects is, in his own phrase, "to help the young soul, add energy, inspire hope, and blow the coals into a useful flame; to redeem defeat by new thought, by firm action." John Tyndall, the eminent English scientist, declared that the reading of two men, Carlyle and Emerson, had made him what he was. He said to his students:

"I never should have gone through Analytical Geometry and Calculus, had it not been for these men. I never should have become a physical investigator, and hence without them I should not have been here to-day. They told me what I ought to do in a way that caused me to do it, and all my consequent intellectual action is to be traced to this purely moral force." After hearing one of Emerson's lectures, James Russell Lowell wrote, "Were we enthusiasts? I hope and believe we were, and am thankful to the man who made us worth something for once in our lives."

Few authors, excepting Shakespeare, have more of the quality of universality in their writings. Many things in Emerson will fit certain stages of individual development as well a thousand years hence as to-day and be as applicable to the moral improvement of the Chinese as of Americans. If he is not as much read in the future, it will be largely due to the fact that his most inspiring subject matter has been widely diffused through modern thought.

Emerson's style is condensed. He spoke of his own paragraphs as incompressible, "each sentence an infinitely repellent particle." Because of this condensation, it is best not to read more than one essay at a time. Years ago some joker said that Emerson's Essays could be read as well backward as forward, because there was no connection between the sentences. The same observation could have been made with almost equal truth about Proverbs, some of Bacon's Essays, Polonius's Advice to Laertes, parts of Hamlet's Soliloquy, and, in general, about any condensed sentences that endeavor to convey a complete, striking truth. Lowell remarks acutely: "Did they say he was disconnected? So were the stars … And were they not knit together by a higher logic than our mere sense could master?" We should look for unity and connection in Emerson's chosen subject matter and trend of thought.

We must not forget that Emerson has in his prose as well as in his verse many of the general characteristics of a poet. In his Essays, he sometimes avails himself of the poetic license to be obscure and contradictory and to present philosophy that will not walk on all fours. When we examine some of the best passages on nature in his early prose, we shall find that they are highly poetical.

Much of his verse is filled with the charm of nature and shows here and there remarkable power of putting great riches in a little room, although there may be intervening waste spaces. Critics may say that his poetry lacks deep feeling, that it is mostly intellectual; if so, it is nobly intellectual. Both his poetry and prose, to use an Emersonian expression, "sail the seas with God."