Also Read

Summary

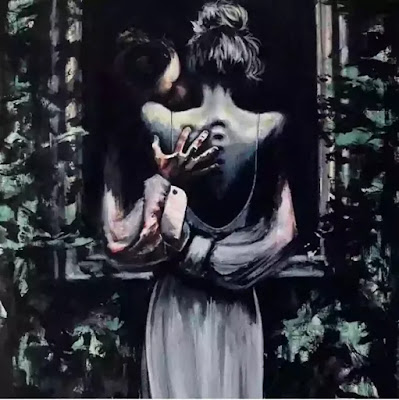

Wuthering Heights is the only novel of Emily Brontë published in 1847. It is unique in the English novel, having no derivative and no successor except in some of the novels of Thomas Hardy. The central figure of the novel is Heathcliff, the owner of the house called Wuthering Heights, severe, gloomy and brutal in aspect and atmosphere, firmly rooted in local tradition and custom. Heathcliff, is, indeed, the human incarnation of the house, primitive, wild and terrific. As an orphan in childhood he was picked up from the streets of Liverpool by Mr. Earnshaw and given asylum in his house. There Heathcliff is brought up as one of the children of the family. A passionate love springs up between him and Catherine, the daughter of Earnshaw. Bullied and humiliated by Hindley the son of Earnshaw, Heathcliff deserts the house on the death of his foster-father.

Returning after three years he finds Catherine married to Edgar Linton, the owner of the Thrushcross Grange, who possesses refinement, kindness, affluence and amiability. Catherine had married him in her superficial attraction for his luxury. Catherine's love for Edgar is only a passing attraction, while in the depth of her heart there burned the consuming passion for Heathcliff. In a famous passage, full of lyrical beauty she explains her feelings thus: "My love for Linton is like the foliage in the woods; time will change it, I'm well aware, as winter changes the trees. My love for Heathcliff resembles the eternal rocks beneath; a source of little visible delight, but necessary. Nelly, I am Heathcliff! He's always, always in my mind; not as a pleasure, any more than I am always a pleasure to myself, but as my own being."

Out of this conflict the whole story proceeds and takes its serious course. Heathcliff to revenge himself upon all those who spoiled all his chances of happiness, married Isabella Linton, Edgar's sister and ill treated her. He had a sickly and repulsive child by her. Catherine had died of child birth, the daughter was Cathy. Heathcliff arranged a marriage between his son and the daughter of Catherine. But the son died. Thus Heathcliff had his revengeful career and was at last worn out and died.

In its bare outlines the novel seems to be a conventional romantic story of love and adventure, "a mixture of brutal melodrama and exaggerated sentiment". But this would be an unfair view of such a terrible, extraordinary book. As an exploration of human passion at different levels and of the effect produced on human life by the interplay of such social levels, the novel is quite new in the history of the English novel. No other novel of the age has penetrated so far into depths of passion or followed. the intensity of its operation to ultimate consequence with such relentless logic. The chief characters in the story are scarcely human beings and defy all psychological analysis, They are elemental forces of nature and passions incarnate. The fusion of nature and man in the story has its parallel only in Hardy's great novels. For its tragic splendour and the beauty and lyricism of style, no praises can be too high. The result of all this is a unique imaginative creation, which ignoring all accepted models of contemporary novel, aspires rather to the simplicity and grandeur of ancient tragedy.

Critical Analysis

Emily Bronte's one and only novel is a remarkable work. It is perfect, and; perfect in the rarest way: it is the complete bodying forth of an intensely individual apprehension of the nature of man and life. That is to say, the content is strange enough, indeed baffling enough; while the artistic expression of it is flawless. Artistically, neither Jane Austen nor Henry James nor Joseph Conrad, the great masters of form in the English novel, did anything to surpass it. And this combination of an intensely individual apprehension and a wonderfully complete formal rendering of it gives it a uniqueness which makes even the fullest and most sensitive discussion of it less than adequate. F.R. Leavis in The Great Tradition has called it a sport. Therein lies the primary difficulty in dealing with it. It is utterly unlike any other novel. There is nothing one can compare it to, for the great masters of form have chosen subjects so different from it as to make Wuthering Heights exist in a category of creation all its own. It can be translated into no alternative terms; the usual compass bearings of criticism do not apply; nor do the usual abstractions the critic makes from the totality of a work go far towards piercing the mystery. No novel is more imbued with the spirit of place than Wuthering Heights, but Emily Bronte makes use of no such set descriptive passages as we find variously in Scott, Dickens, George Eliot, Hardy, or Lawrence. The reality of her characters cannot be questioned, but their reality is of an utterly different kind from either Dickens's, Thackeray's, Trollope's, George Eliot's, or Henry James's. Nor does the style, which is a novelist's speaking voice, help: it is perfect for her purpose, but it is as plain as the most limpid of spring water. More than with any other novel we are faced, in Wuthering Heights, with a totality, a work that is whole as a great lyric poem is whole and that cannot be separated into parts. And in a sense the author is not there at all: this most individual is also the least idiosyncratic.

Publication. Emily Bronte wrote one novel, Wuthering Heights, and her fame rests upon it. This novel which grips the mind of any appreciative reader was written by a woman in her late twenties who looked at life through the narrow windows of a vicarage. Her knowledge of the outside world, beyond the moors and hills in its neighborhood, was negligible. In 1846, Charlotte, Emily and Anne — (the Bronte sisters) produced a Volume of poems under the pseudonyms "Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell". Although many of the poems are today well esteemed, they were at the time an utter failure. In 1847, Charlotte came out with Jane Eyre under the pen-name of Currer Bell. In the same year, Emily completed Wuthering Heights published under the name of Ellis Bell.

Sources. There has been much speculation among critics about the possible origins for the plot of Wuthering Heights. Emily is reported to have read a German story by Hoffman in which a stranger spends a night in a forbidding manor, sees a ghost and later learns its story.

Another source suggested is that Emily heard of a neighboring estate which came into the possession of a certain Jack Sharp, through unscrupulous practices which included marrying, successively a mother and a daughter. (Heathcliff marries to gain possession of an estate, and subsequently makes his despised and dying son marry the daughter of the woman he loved, to get the rest of it.)

Some of the incidents are inspired by Emily's own experience. Of particular importance in this respect is Emily's brother, Branwell. Aspects of her brother's character appear in the cynical, hyper-sensitive, self-pitying Linton; to Heathcliff, she lends touches of the jealous and baffled lover; and he is especially seen in the development of Hindley's personality, passing from spoiled childhood through reckless, selfish and self-indulgent youth to drunkenness, ineffectual violence, weakness and despair. The death of Emily's eldest sister Maria on 6 May 1825 is also of significance. Maria had been a little mother to her brother and sister, and the boy Branwell declared after her death that he had heard her crying outside the windows at night. Perhaps this provided the inspiration for that moving and frightening scene in Wuthering Heights where the 'ghost' of Catherine Earnshaw disturbs the peace of Lockwood (and Heathcliff) as she clamors to come in at the window.

The Setting. The scene of Wuthering Heights is laid in the bleak moorland country of the West Riding of Yorkshire. In almost every chapter emphasis is laid on the bitter winds and storms, the impassable roads, the marshes and weather and the wild birds of this region. The geographical setting plays a major part in providing the atmosphere for the unfolding of the action. Mainly pasture land for the grazing of sheep and cattle, this part of Yorkshire, even today, is sparsely populated and the dreariness of the climate is reflected in the dour, unsociable characters who people the novel.

Period of Action. The action in the novel spans the year 1778-1802 an age which covers the early phases of both the "industrial revolution" in England and the French Revolution and Napoleonic wars on the Continent. But these momentous historical events play no part in the development of the plot.

The Theme. The underlying universal theme of Wuthering Heights is the co-existence of good and evil. Like Shakespeare's Hamlet, this novel is concerned with the problem of men and destiny; and like Milton's Paradise Lost, it recalls the proud change of Satan and the conflict between good and evil which had dominated man's entire history. The interaction of the two families— The Earnshaws and the Lintons, exemplifies the co-existence of truth and falsehood, of love and hatred, joy and sorrow, health and sickness, heaven and hell. Eventually the good conquers evil in Wuthering Heights. In Heathcliff, one sees the conflict between his all-demanding love, which when frustrated turns into vindictive resentment, find an all-consuming hatred.

However, there are a series of minor themes which work on several levels at once. According to Hilda. D'Spear, it is about love and jealousy and revenge, about loss and desire; it is about selfishness and self-willedness, about cruelty, violence and fear, about the evils of drunkenness, about the bringing up of children and education; it is about books and religion, about freedom and subjugation, about untamed nature and the conceptions of society; about happiness and misery, about alienation, about sickness and death, it is about the strange and the supernatural, about the homely and the familiar; and finally it is about a spiritual accord which defies separation and death to achieve reconciliation in a life beyond the grave.

The Story. It revolves round the hero of Wuthering Heights—Heathcliff—a man as stormy and wild as the Yorkshire moors in which the story is set. Brought as a waif by Mr. Earnshaw to the Heights, he is reared with Earnshaw's two children, Hindley and Catherine, Heathcliff and Catherine share an intense love while Hindley and Heathcliff develop intense hatred as Heathcliff supplants Hindley in his father's affections. On the death of Earnshaw, Hindley returns with a wife, Frances and tyrannizes the household and particularly ill-treats Heathcliff. Frances dies giving birth to Hareton. Heathcliff dire straits is even more pitiable, when Catherine makes the acquaintance of Edgar and Isabella Linton of Thrushcross Grange. Eventually, Catherine marries Edgar though she still loves Heathcliff and from then on Heathcliff is irredeemable. He leaves the Heights and returns a few years later as a well-bred gentleman. He still bears his passionate love for Catherine but coupled with it is his intense desire for revenge against the families of both the Earnshaws and the Lintons. To this end, he marries Isabella, ill-treats her and finally when she leaves him giving birth to a son Linton, he claims his son on her death. Catherine also dies giving birth to a daughter who is also named Catherine. Heathcliff's plan of revenge takes a diabolic turn when he gets his sick son Linton to marry Catherine so that he can get the property of the Grange. Linton dies very soon and Catherine is left a young widow in a hostile home. Hareton Earnshaw who had been ill-treated by Heathcliff in the same way he had been ill-treated by Hindley, is attracted to Catherine and eventually, their love ends in marriage. Heathcliff himself dies and is buried by the side of his beloved Catherine. He is united with her in death. Love triumphs over the desire for revenge in the story. Thus, the novel ends on a positive note.

The story is told in the first person by two main narrators, the tenant Lockwood who tells of the present and his housekeeper Nelly Dean who recounts the past. A diary kept by the elder Catherine, letters written by Isabella, and information given by Zillah, the new housekeeper at the Heights, fill in additional information.

Film Version. A full-length film version of Wuthering Heights was produced and directed by William Wyler in 1942, with Merle Oberon as Catherine, Laurence Oliver as Heathcliff. David Neven as Edgar Linton and Flora Robson as Ellen (Nelly) Dean.

Wuthering Heights, the story of one man's passionate love and devilish hate is relevant for all times, though the world Heathcliff inhabited may have disappeared in the geographical sense. Human nature changes but little, and all of us have within us the instincts, the capacities, the passions and the responses which are felt and articulated by the characters in Wuthering Heights. We may conclude with the words of the poet Swinburne, a great admirer of the Bronte sisters; he said. "It may be true, that not many will ever take it to their hearts; it is certain that those who do like it will like, nothing very much better in the whole world of poetry and prose."

Emily Bronte's Mysticism. The central fact about Emily Bronte is that she is a mystic. Wuthering Heights itself is not the record of a mystical exercise; for in dictations of that we must go to their poems; but the novel is the statement of the conclusion derived from her experience. What they are it is not easy to say; she was neither a philosopher nor a theologian but a novelist; in Wuthering Heights she symbolizes the findings of her intuition into the nature of things, but not in a way from which we can generalize. Interpretation of the novel, therefore, will differ with every reader who approaches it. But we are surely shown the universe as the scene and expression of two opposed principles which, even though they seek to devour each other, yet ultimately compose a harmony. They are symbolized in the novel in the two house and their occupants, Wuthering Heights on its bleak eminence, "Wuthering being a significant provincial, adjective descriptive of the atmospheric tumult to which its station is exposed in stormy weather", and Thrushcross Grange in the far valley, below. They stand respectively, though any label is inadequate and is 'shorthand' only, for the principle of energy and storm on the one hand and the principle of calm, of settled assurance, on the other. And they are not only principles, they are as it were elements: the children of one cannot breathe in the other. As Catherine Linton says of her relationship with Linton Heathcliff:

One time, however; we were near quarreling. He said the pleasantest manner of spending a hot July day was lying from morning till evening on a bank of heath in the middle of the moors, with the bees humming dreamily about among the bloom, and the larks singing high up overhead, and the blue sky and bright sun shining steadily and cloudlessly. That was his most perfect idea of heaven's happiness: mine was rocking in a rustling green tree, with a west wind blowing, and bright white clouds flitting rapidly overhead; and not only tasks, but thrushes and blackbirds, and linnets, and cuckoos pouring out music on every side, and the moors seen at a distance, broken into cool dusky dells; but close by great sweets of long grass undulating in waves to the breeze; and woods and sounding water, and the whole world awake and will with joy. He wanted all to lie in an ecstasy of peace; I wanted all to sparkle and dance in a glorious jubilee. I said his heaven would be only half alive; and he said mine would be drunk; I said I should fall asleep in his; and he said he could not breathe in mine.

The Two Worlds of Wuthering Heights. The two principles, these two worlds, might have existed side by side in peace if the outsider Heathcliff had not been introduced into Wuthering Heights by Mr. Earnshaw, the old master. His history, as Nelly Dean says is 'a cuckoo's'. Yet Nelly is scarcely fair to Heathcliff. Circumstances have made him a cuckoo. On one level Wuthering Heights is a novel of revenge, with Heathcliff the avenger, but he has become one solely because of his treatment at the hands of Hindley Earnshaw and the resulting frustration of his passionate affinity with Catherine Earnshaw. It is the frustration that leads to his great scheme of revenge on the Earnshaws and Lintons alike and his winning of their properties. Heathcliff is not a monster; he is much more a primordial figure of energy. He and Catherine Earnshaw may be compared to two rivers that are brought by every configuration of territory to flow into each other; but their courses are diverted, their proper channels dammed, and for Heathcliff, the consequence is the destruction of everything lying in his path; energy obstructed is energy perverted. When in the end Heathcliff is joined with Catherine the harmony, the balance, is restored; the evil set up by obstructed energy has worked itself out.

By then, however, Catherine Earnshaw has been dead for several years and is a ghost. Our first introduction to her in the novel is has to a ghost, and almost our first introduction to Heathcliff is as to a haunted man. Emily Bronte's province is reality, but spiritual reality; in Wuthering Heights death is not an end but a liberation of the spirit, and in the world of Wuthering Heights those we normally call the living and the dead exist side by side and are in communication. Yet we do not think of Wuthering Heights as an exercise in the supernatural as some of Stevenson's and James's stories are; because Emily Bronte makes no distinction between the natural and the supernatural; her world is one and, rendered ever so concretely as it may be, it is a spiritual world.

This explains why the characters and their actions, on the face of it so incredible, convincing as they do. Heathcliff and Catherine Earnshaw are as real as any personages in fiction, but they are real in a way different from any others; those that have the closest relationship to them are some of Dostoevsky's and Herman Melzille's. The reality of Fielding's characters, of Jane Austen's, Thackeray's, Trollope's, or Arnold Bennett's might be called a sociological reality; the reality of George Eliot's characters, like those of and Lawrence, is primarily psychological, though no hard and fast separation between the two kinds can be made. But Emily Bronte's world and its inhabitants have nothing to do either with sociology or with psychology; her world is determined by spiritual values which are embodied in the characters. This does not make them less real; does make them real in a unique way. They convince because they so completely express in themselves and their behavior the laws of their being, which are their creator's deductions artistic deductions—from the findings of institution into the nature of things. The intuition was grasped with complete certainty and in detail; if it came as a flash of light then it lit up the whole of life, and what was seen thus illuminated was remembered as well as the illumination. The proof of this is the very concreteness of Wuthering Heights and its flawlessness as a totality. Everything in the novel works together to produce the concreteness, the characters, the action, the kinetic prose that renders a whole landscape and geography and climate without ever becoming, except for phrases, ’descriptive'. "Wuthering Heights", E.M. Forster has said in Aspects of the Novel' “is filled with sound-storm and rushing wind." The storm and rushing wind are conveyed by no set pieces but are in the words themselves of the novel, in its imagery of bent thorn-trees, and in the characters. Wuthering Heights is a novel conceived at the highest poetic level, and her great characters are dynamism of a kind we find normally only in the greatest dramatic poetry.

Superb Technique. Yet superb as the conception of Wuthering Heights is, it is easy to imagine one similarly superb being botched in its execution. Wuthering Heights is anything but botched: the conception is matched by a technique equally superb. To find anything to rival it we have to wait for the arrival of Conrad half a century later; in fact, Emily Bronte anticipates uncannily Conrad's characteristic methods of narration as we find them in Lord Jim and Chance and goes into even subtler degrees of complexity. As we begin to read the novel the action is already approaching its end, poised on the edge of climax. We first see Heathcliff through the eyes of the narrator Mr. Lockwood, the outsider from the south who has rented Thrushcross Grange from him. We share in Lockwood's bewilderment and curiosity at the strange situation at Wuthering Heights, and through him, we feel the full impact of Heathcliff's intransigent spirit. But it is from Nelly Dean, the housekeeper at Thrushcross Grange and a former servant at Wuthering Heights, that Lockwood hears the whole apparently tragic story—one says 'apparently' because finally, the novel is not tragic but something for which we lack a word, though perhaps heroic is the nearest we can get—through the years down to the actual time of narration. Nelly has been the closer observer of the action, of Heathcliff's arrival, his brutalization by Hindley Earnshaw, his revenge on him and on Edgar Linton, who marries Catherine Earnshaw, and his deliberate attempts to bring down and degrade both families as he himself had been degraded. To some extent Nelly has even been Heathcliff's confidante, as she has certainly been both Catherine Earnshaw's and her daughter Catherine Linton's; she has also, as servant and tool, played her small part in the action, though she is spiritually outside it; she is at once narrator and chorus, and what she narrates she does with awe. Emily Bronte incorporates within Nelly's account other narratives in the first person, young Catherine Linton's and Isabella Linton's. Then Lockwood abruptly leaves Thrushcross Grange, disgusted with the weather. When he returns to the neighborhood some months later curiosity again drives him to Wuthering Heights. He finds the atmosphere and situation there curiously changed, and Nelly, installed there as housekeeper, again tells him what has occurred.

As in Conrad, this complex method of relating the story serves a complex purpose. The device of plunging us into the action while it is well underway is as old as epic, but it always dramatizes it and keys up the suspense: our curiosity is piqued as Lockwood's was. We are compelled to identify ourselves with Lockwood and the effect of our seeing everything partly through his eyes and partly through Nelly Dean's is, as it were, to see the action framed, almost as though on a stage; while the enormous curiosity of the sophisticated southerner and the awe of the simple peasant woman become themselves a tribute to the intensity of the drama whose unfolding is being reported; they serve not merely to heighten the drama but to underline its significance and its scope, for Lockwood and Nelly are essentially spectators. That is the role forced on us, the readers, and their comments, their function as chorus, become ours too. Emily Bronte puts us, so to speak, in our place at the very beginning; her technique dictates what we shall see and also how we shall respond to what we see. It is this that gives Wuthering Heights its singular richness, which can only be compared in its total effect to that of Shakespearean tragedy; for at the end of the novel, which as novels go is quite short, all we can say is something like the last lines of Lear:

We that are young

Shall never see so much, nor live so long.