Also Read

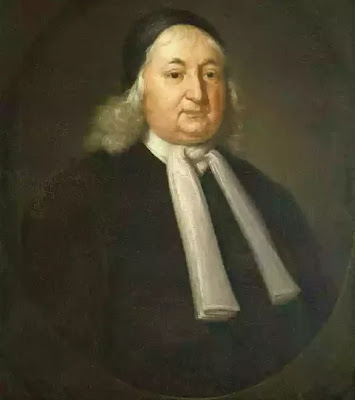

Samuel Sewall, who graduated from Harvard in 1671 and finally became chief justice of Massachusetts. He born in 1652 at Bishopstoke, Hampshire, England, a boy who sailed for New England when he was nine years old, and who became our greatest colonial diarist.

His Diary runs with some breaks from 1673 to 1729, the year before his death. Good diaries are scarce in any literature. Those who keep them seldom commit to writing many of the most interesting events and secrets of their lives. This failing makes the majority of diaries and memoirs very dry, but this fault cannot be found with Samuel Sewall.

His Diary will more and more prove a mine of wealth to the future writers of our literature, to our dramatists, novelists, poets, as well as to our historians. The early chronicles and stories on which Shakespeare founded many of his plays were no more serviceable to him than this Diary may prove to a coming American writer with a genius like Hawthorne's.

In Sewall's Diary we at once feel that we are close to life. The following entry brings us face to face with the children in a Puritan household:—

"Nov. 6, 1692. Joseph threw a knop of brass and hit his sister Betty on the forehead so as to make it bleed and swell; upon which, and for his playing at Prayer-time, and eating when Return Thanks, I whipped him pretty smartly. When I first went in (called by his Grandmother) he sought to shadow and hide himself from me behind the head of the cradle: which gave me the sorrowful remembrance of Adam's carriage."

Sewall was one of the seven judges who sentenced nineteen persons to be put to death for witchcraft at Salem. After this terrible delusion had passed, he had the manliness to rise in church before all the members, and after acknowledging "the blame and shame of his decision," call for "prayers that God who has an unlimited authority would pardon that sin."

Sewall's Diary is best known for its faithful chronicle of his courtship of Mrs. Catharine Winthrop. Both had been married twice before, and both had grown children. He was sixty-nine and she fifty-six. No record of any other Puritan courtship so unique as this has been given to the world. He began his formal courtship of Mrs. Winthrop, October 1, 1720. His Diary contains records of each visit, of what they said to each other, of the Sermons, cake, and gingerbread that he gave her, of the healths that he drank to her, the lump of sugar that she gave him, of how they "went into the best room, and clos'd the shutters."

"Nov. 2. Gave her about 1/2 pound of sugar almonds, cost 3 shillings per [pound]. Carried them on Monday. She seem'd pleas'd with them, ask'd what they cost. Spake of giving her a hundred pounds per annum if I died before her. Ask'd her what sum she would give me, if she should die first?"

"Monday, Nov. 7. I went to Mad. Winthrop; found her rocking her little Katy in the cradle. I excused my coming so late (near eight). She set me an arm'd chair and cushion; and so the cradle was between her arm'd chair and mine. Gave her the remnant of my almonds. She did not eat of them as before…. The fire was come to one short brand besides the block, which brand was set up in end; at last it fell to pieces and no recruit was made…. Took leave of her…. Her dress was not so clean as sometime it had been. Jehovah jireh!"

Acute men have written essays to account for the aristocratic Mrs. Winthrop's refusal of Chief-Justice Sewall. Some have said that it was due to his aversion to slavery and to his refusal to allow her to keep her slaves. This episode is only a small part of a rich storehouse. The greater part of the Diary contains only the raw materials of literature, yet some of it is real literature, and it ranks among the great diaries of the world.

Samuel Sewall’s Diary, which records the events between the years 1674 to 1729, is quite lively. Sewall fits the pattern of early New England writers, having seen in Bradford and Taylor. Born in England, Sewall was brought to the colonies at an early age. He was the son of the New England settlers. He came from England to Boston with his family in 1661 and made his home in the Boston area and he graduated from Harvard. Soon after his education, he took up a career of legal, administrative, and religious work. He distinguished himself as a humane and liberal jurist, most notably while he was still a Chief Justice. His writings testify to that reputation. The Revolution in New England Justified (1691), written in conjunction with Edward Rawson, justifies the uprising of 1689, which deposed the Royal Governor Andros. The text conceives of New England as the eventual seat of Jerusalem. Phaenomena Quaedam Apocalyptica (1697) followed. Sewell went on to write one of the earliest published arguments against the slavery in The Selling of Joseph (1700). In 1713, he produced another theological treatise Proposals Touching the Accomplishment of Prophecies (1713). He was born late enough to see the change from the early strict religious life of the Puritans to the later, more worldly Yankee period of mercantile wealth in the New England colonies. His Diary often compared to Samuel Pepys’s English diary more or of the same period, inadvertently records the social transition. It is a most significant historical document. Like Pepys’s Diary, Sewall’s is also a minute record of his daily life, reflecting his interest in living piously and well. He records even little purchases of sweets for a woman he loved, their disagreements over whether he should affect aristocratic and expensive ways such as wearing a wig and using a coach. Easier to read than the highly religious poetry, it is full of the biblical references. These historical and secular accounts recount real events with the use of lively details of the ordinary life.

The stronghold of the Puritanism was waning in New England before the end of the 18th century. The number of un-churched colonists had been large. There was also a steady rise in the people’s standard of the living. The Great Awakening’, however, was a itself a reaction of what was rightly felt to be dominant trend. The growing tendency of the colonists was to accept the ideas of Enlightenment. The ideas emphasized the influences of reason and commonsense and also imperatives of self-help, personal and social progress. The new generation of immigrants was very eager to improve their lot in a new land. For vast majority who never heard of Enlightenment, the gospel of reason was commonsense. Profit and progress became the part of the American way. These two writers of this period are - William Byrd of Westover and Sarah Kemble Knight. They suggested secular tendencies in their travel accounts.

Before the revolution, there was early literature in the South which was also secular and aristocratic in its nature. It reflected the ethos of the dominant social and economic systems of the southern plantations. Because of economic opportunities, not because of religious freedom, the English immigrants were drawn to these colonies. The southerners are poor fanners or trading people living not much better than their slaves. The southern literature of the upper class was shaped by the classical old world ideal of a noble, the landed gentry made possible by the slavery. The institution released wealthy southern whites from manual labor, afforded them leisure and the made the dream of aristocratic life in the American wilderness. The puritan’s emphasis is on the hard work, education and earnestness. Instead of that, we hear of such age old pleasures as horseback riding and hunting etc,. The church was the focus of the genteel social life, not a forum for fighting over the religious ideas.

Sarah Kemble Knight (1666-1727) and William Byrd of the Westover (1774-1744), in their poetry, suggested increasingly secular tendencies of this period. Both Knight and Byrd wrote accounts of their journeys through the parts of America and tend to concentrate on the social issues, the curious people and manners they encountered along the way.